‘Hot Spring Shark Attack’ Review

There’s plenty of reason to be skeptical about movies like Hot Spring Shark Attack in a post-Sharknado world. Perhaps it’s that we became accustomed to being terrified of sharks that we needed a tornado full of them. However, The Asylum’s absurd premise led to multiple sequels, all of which are now largely forgotten. Before that, the best shark movies could be counted on one hand, and the worst ones took too much effort to remember. The common thread is that America has dominated the subgenre. Once The Asylum got its hands on it, though, the genre became flooded with parodies that rarely stray from a formula. For that reason, Japan’s entry into the subgenre feels refreshing and endearing amidst the atrocious comedies and tedious thrillers (with a few exceptions, of course, such as this year’s Dangerous Animals).

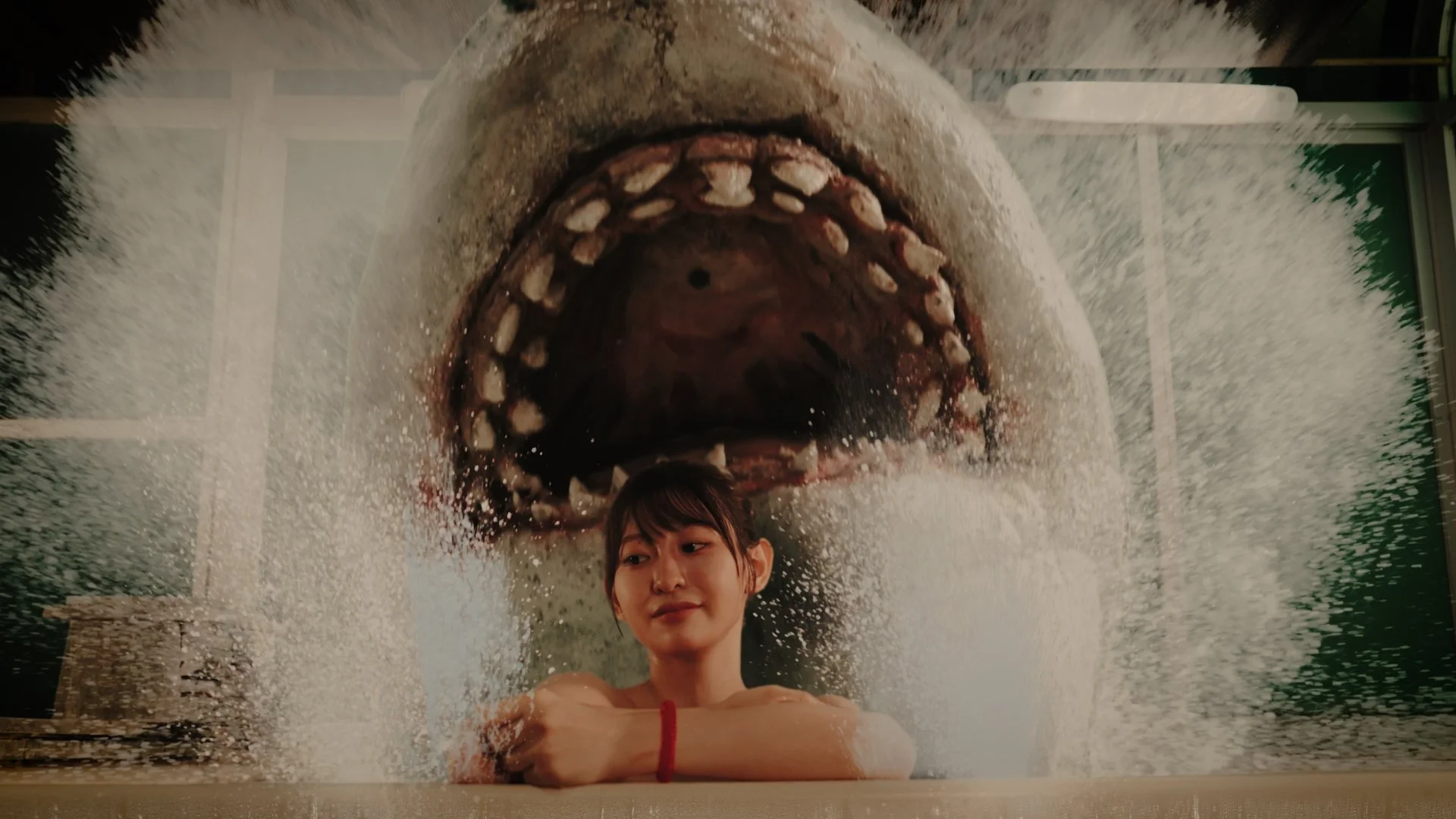

Morihito Inoue’s Hot Spring Shark Attack is the kind of insane, low-budget horror-comedy that dares to dream bigger than its financial circumstances can allow. Atsumi, a seaside town that is home to a bounty of hot springs (known as ‘onsens’ in Japan, and why the Japanese release of the film is simply titled Onsen Shark), begins construction on a new resort intending to encourage tourism and live up to its moniker as the “Monaco of the East.” At the helm of the project is a mayor whose obsession with maintaining a popular image draws the ire of Atsumi’s citizens, and is further exacerbated when shark attacks are reported within the city. However, the nature of the attacks is suspicious as bodies are located in the ocean, but their injuries indicate something far grislier might be happening.

Of course, as the title suggests, and the film wastes zero time getting at: sharks are attacking people in hot springs. A film littered with police simply “too old for this shit,”, scientists too excited by the potential discovery, and influencers more concerned with getting views than staying alive, Hot Spring Shark Attack makes it very clear that it is not trying to be anything more than its name implies. It’s a silly film that draws from its inspirations while approaching its subject matter in a tongue-in-cheek manner. Still, there’s an effort put into explaining the logistics of sharks entering hot springs and why these particular sharks are more frightening than even a great white, which elevates the danger felt by the characters without ever spilling over into the audience. There are plenty of tonal shifts, but Inoue leans into them so hard that something outlandish on paper is even more insane to witness on screen. It does frequently avoid delving too deeply into its characters, but with a 77-minute runtime and numerous ideas, it’s not only understandable but also a welcome omission.

The reason Hot Spring Shark Attack is better than many other shark movies that have come before it is that Inoue doesn’t seem to be making fun of the genre or the film’s concept. There’s a self-awareness in that Inoue knows how outlandish the film is but commits to the bit in a way that all the terrible CG and hilarious use of miniatures amplify the experience more than it detracts. A police officer pulls out a gun and shoots the words “No Swimming Allowed” into the sand of a nearby beach instead of putting up a sign because there’s urgency in what needs to be done; it’s just a silly way to do it. The cast, which includes Daniel Aguilar, Takuya Fujimura, Shôichirô Akaboshi, Kiyobumi Kaneko, and others, is all having fun with the absurdity of the situation in their performances. The experience hews closer to witnessing a cult film with a midnight crowd, with the closest comparison being Shin'ichirô Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead. Inoue’s film builds to the outlandish as a result of people doing things in absurd ways, and each subsequent action further develops a ridiculous situation until there’s just nowhere to go but outside the confines of normalcy.

While it may be the case that Hot Spring Shark Attack is a fun movie, there is no denying that even a constant build of zaniness can be exhausting and downright dull at times. Jokes often land with a thud, though it occasionally makes the characters more endearing than hurting the film. It’s all about striking a balance between creating a movie and crafting an experience. Inoue comfortably shifts into creating the latter and builds it all upon the narrative framework of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. That it features many elements from Spielberg’s film is unsurprising, but what is impressive is how well the low-budget visual effects and creativity breathe new life into a relatively stale genre. Everyone walking into the film will expect non-stop silliness, but Inoue injects a creative energy and endearing approach into a goofy celebration of cinema that needs to be seen to be believed.